Wolfram's Automata, Atoms of Complexity

Cellular Automata are really amazing things. The best introduction to Cellular Automata in my opinion is the story of Stephen Wolfram and the rule 30 automaton. It goes like this:

Wolfram was a young student performing computer experiments. He had the idea for an experiment that could count through the binary digits of a number, and use the bits as instructions for a simple automation.

I don’t know exactly what motivated him to do this, but I like to think that it was an artistic sort of motivation. The experiment was not completely straightforward in implementation, but very simple in underlying concept.

Basically the idea is to encode a policy for an agent or cell in a simulation. Depending on what state of the world the agent experiences, it will perform an action. One example might be a simulation where agents can move around in space, and move towards food or away from danger. Some have taken this kind of research to great heights, and have found ways to represent very complex decisions by modeling very complicated states where agents can execute complicated policies. A.I. research.

Wolfram’s experiment goes the other direction. What is the simplest possible agent? What is the simplest possible state, and what can we learn by understanding the elementary pieces of this puzzle?

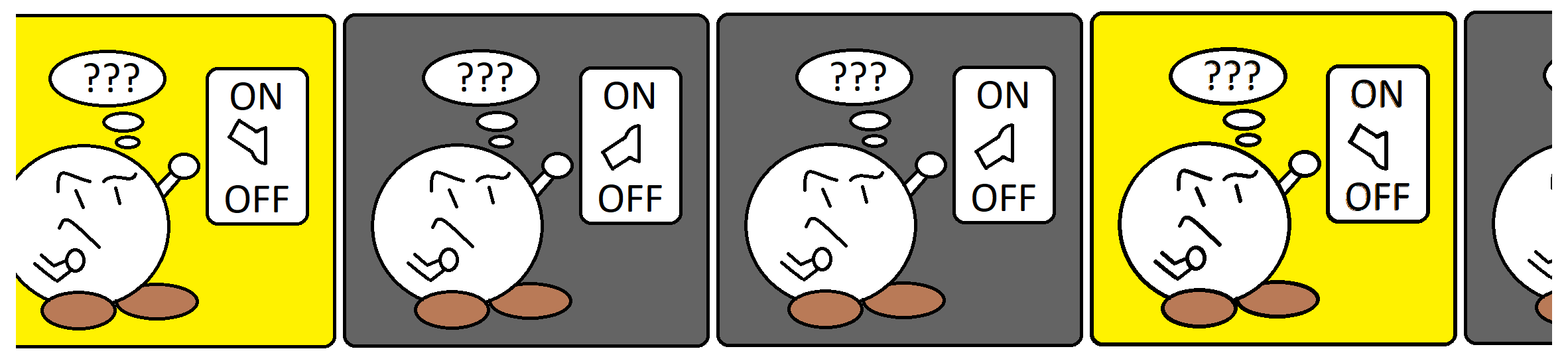

In Wolfram’s experiment, the agents cannot move. Their entire world is just one row of cells, like one row of keys on a keyboard. The action each cell can perform is very limited. Each cell is locked in place, but each has a light that it can turn on or off.

In addition. the perception of each cell is very limited. It can see its neighbor to the left, its neighbor to the right, and itself. For each cell nothing else is visible, and it has no memory besides its ability to see whether its own light is current off or on.

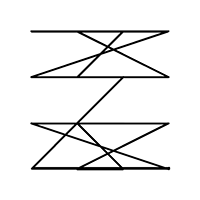

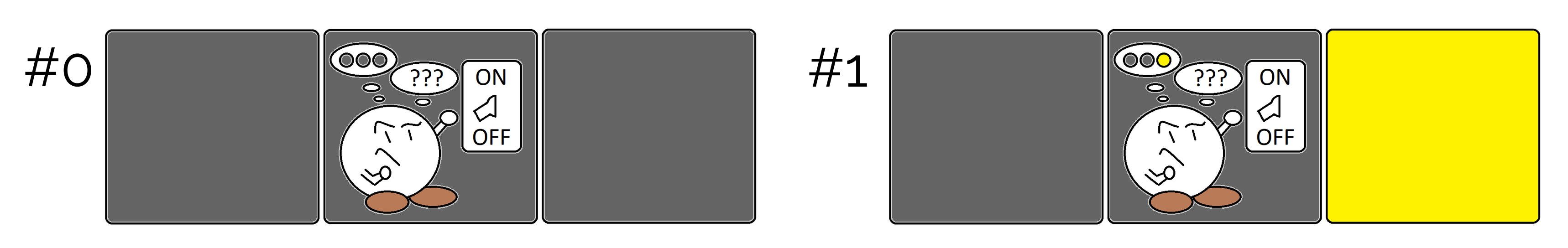

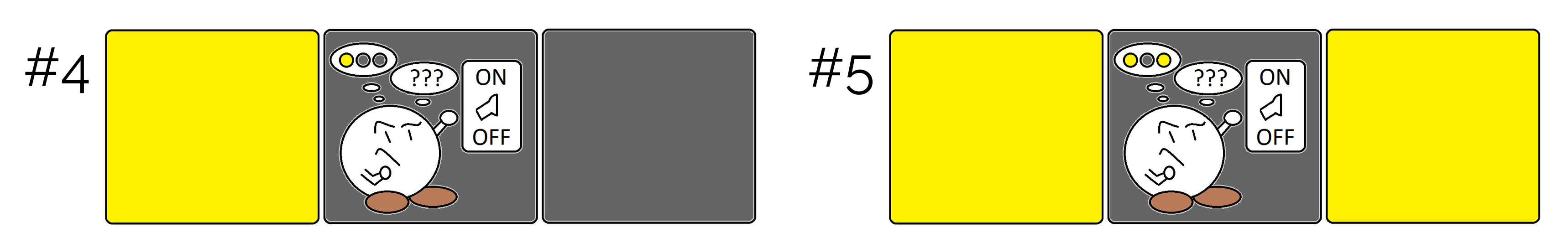

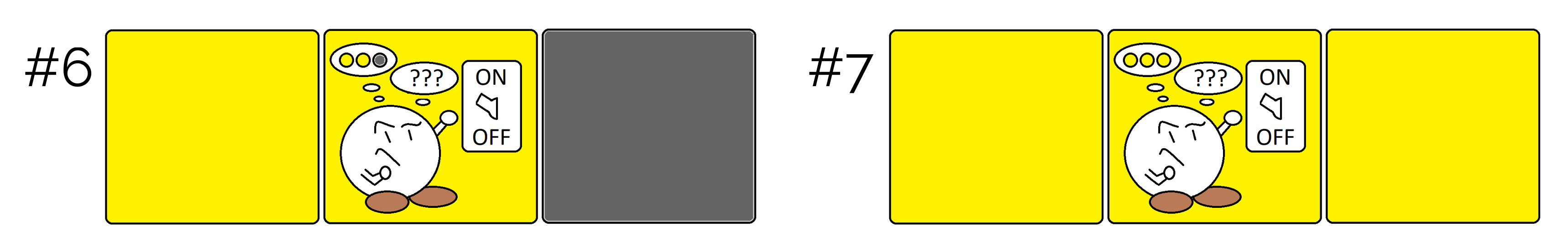

This means with three inputs combined, each cell can only have 8 possible experiences. Every binary number 0-7 corresponds directly to a state of the world our little cell might see. Maybe all three cells are dark, maybe all three cells are lit, or maybe something in between. Whatever might occur, it must be one of 8 possibilities.

Here we can see the 8 possible neigborhoods. Why not label them 1 - 8? Its a stylistic choice. This way it may be confusing that the last one is labeled #7 when there are eight of them, but it has the distinct advantage that the labels match the binary number you get by directly reading the cells as binary bits.

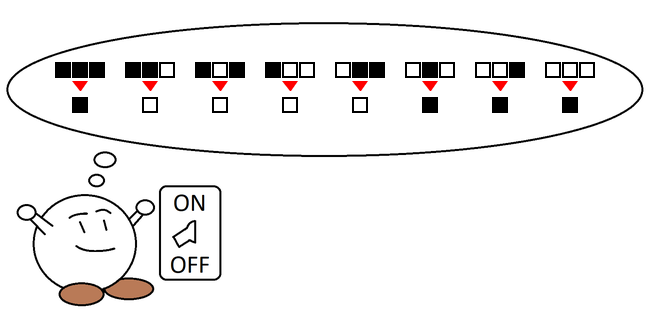

With only 8 possible experiences for our agent, and two possible actions, it becomes feasible to define a policy that will completely describe its behavior. If we assign one action for each state or experience, it only takes 8 of those assignments to completely describe its behavior.

This means that for our agent, if we start with an 8-bit number, we can break that number down bit by bit and completely derive the policy. Wolfram called these 8 bit numbers the “rules”, and there are as many rules as there are 8 bit numbers. 256 rules.

Some people find this confusing to call this number the singular “rule”, because technically each rule is a set of 8 sub-rules. One sub-rule from each bit mapped to each possible environment. The 8 bit number is called a rule, not for a technical reason, but because with our experiment we intend to study many different sets of rules, not just one.

When contrasting rule 29 with rule 30, for example, it is simply easier to say “rule” instead of rule-set, even if the latter might be more technically accurate.

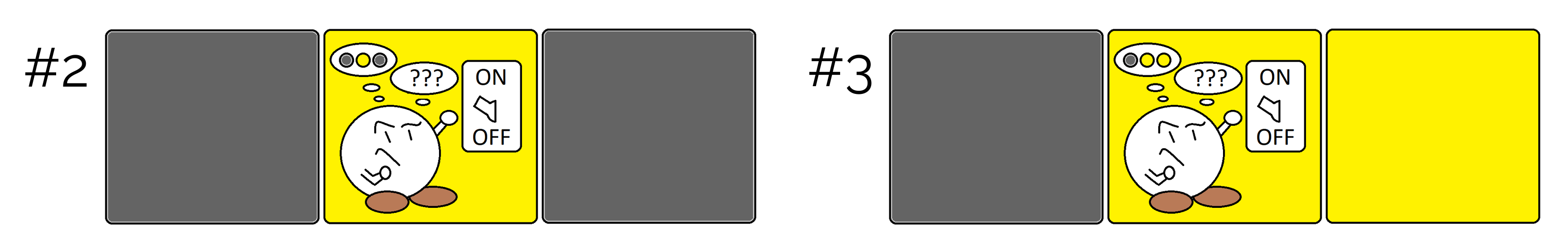

If we record cells over time, it’s possible to draw a picture using the horizontal space to show our cells, but also using vertical space to represent time passing. One way to think of it is the agents are walking forward or falling down into a fresh set of cells, leaving a record behind them of what they have been up to.

Now that we understand the relationship between the rule and one cell, i.e., one agent, the true objective of Wolfram’s experiment can come into focus. There is nothing particularly interesting about the behavior of one agent with any specific 8 bit rule. But the purpose of this experiment is to observe the behavior of an ensemble of agents all operating collectively, not just one. To see what dynamics are present across the entire set of all 256 rules, not just any one rule in a particular.

The initial row of cells at the top, red arrows, and policy for each neigborhood at the bottom are interactive. Try clicking!

Graphing the automation over time, we can draw an image that shows the behavior of each rule. Each row of the image is the same row of cells, but the columns show how those cells change state over time. Some rules produce lines, pyramids, or even repeating geometric patterns like Sierpinski’s triangle. But they exhibit some very unexpected behavior as well. Chaotic behavior, noise, and turbulence. Dynamic balances between chaos and order. True and unlimited complexity.

When he first saw the turbulent chaos of rule 30, Wolfram was shocked. He only expected to find simple patterns produced by the simple 8 bit rules. Perhaps there was some error? But it was a simple matter to look up the rule and verify the pattern by hand. The 8 bit rule 30 truly does produce this turbulence.

Most people would have been surprised, in fact many people are still surprised because it challenges a basic assumption about the nature of turbulence. The conventional wisdom is that the turbulent phenomena magnify existing turbulence that is already there but at a smaller scale. So the force of a wing through the air might provoke a mess of air currents, but all of this just represents a previous mess of brownian motion that has been amplified. Nevertheless, a conventional understanding would infer that causal continuity exists between large scale features of some turbulent system and smaller features of the microscopic dynamics that existed previously.

Rule 30 shows that these features of turbulence do not need to previously exist at all. They are spontaneously created by the automation iterating over time. This means that they are fundamentally new structures in the world. Although they might be sensitive to microscopic differences in the previous state, that does not mean they are described or caused by those differences.

Rule 30 proves this by counterexample. How could the chaotic behavior in this automation be described or caused by microscopic features that do not exist in this model?

Cellular Automata like rule 30 or rule 110 seem to capture a very complex problem, but one that can be represented as the sum of many simple operations. This phenomenon poses a challenge to reductionistic methods of science. Many things about these Cellular Automata remain uknown even though the smaller parts involved are completely described. A little fragment of nature’s hidden magic, working in binary and avalible on your computer screen.